Garmin iQue 3600: How A Palm OS PDA with GPS Predicted The Future

How do you get the-ah from hee-ah? Here in Userlandia we’re piloting a car with Palm OS.

It’s hard to get lost nowadays. After forty-odd years of research and development we’ve finally arrived at our science fiction future where magic devices pulled from our pockets can pinpoint our positions precisely. But as revolutionary as they are, smartphones are just the latest milestone in a long trail of satellite navigation tools. Milestones like this: the Garmin iQue 3600.

At first glance it looks like a normal Palm OS personal digital assistant with its normal apps. But there’s something about it that most PDA users don’t know about. It has a secret—a GPS antenna! Garmin released the first StreetPilot portable automotive GPS in 1998, so it’s only logical that they were the first to combine a GPS with a PDA. The iQue was announced at the January 2003 Consumer Electronics Show and shipped six months later at an MSRP of $589. That seems high for a PDA, but consider how much it cost to buy comparable devices. A Palm Tungsten T2 was $399 and a Garmin StreetPilot 2610 was $799, so the iQue combining both of them into one device for half the price seemed like quite the bargain.

I found this one complete in box at the thrift store for $13, and I couldn’t resist bringing it home. Inside that box is the PDA itself, a dashboard mount with car charger, HotSync Cradle, software CDs, and manuals. The only item that appears to be missing is the leather flip-cover, which is too bad because half the fun of a PDA is flipping the cover open like Lois Lane when she’s jotting down a big scoop.

From a design standpoint the iQue doesn’t stand out from the crowd of silvery rectangular PDAs. It’s got the same aura as a silver Toyota Camry: practical, reliable, and tasteful. Such designs were popular because there were two kinds of people who bought PDAs: geeks and traveling businesspeople. They could take out a subtle silver PDA on location or at a business meeting and not feel like they’re waving money in their clients’ faces. If Garmin showed these road warriors a pocketable device that told them how to get from point A to point B in unfamiliar territory, they’d scream “shut up and take my money!”

What the iQue lacks in flash it makes up for in function. There’s a bevy of buttons for quickly controlling its intuitive interface. Three of the four standard Palm face buttons are there—the Date Book, Address Book, and Todo List—and the fourth cycles through Garmin’s GPS-enabled apps like the QueMap, QueTurns, and GPS status. On the side of the device is a shortcut button for recording voice clips, a scroll rocker, and an escape button for backing out of dialogs or returning to the home screen.

Garmin also included decent connectivity options. Along the top is a headphone jack, an SD card slot, an external GPS antenna port, and an infrared transceiver for wireless data transfer. On the bottom is the Palm Universal Connector for attaching cradles, keyboards, and accessories designed for Palm devices. The included USB HotSync cradle is surprisingly hefty due to its metal construction. A car cradle is also included, complete with a charger and a beanbag to keep it planted on your dashboard.

The integrated GPS receiver adds some thickness, but Garmin’s designers styled it to minimize its impact. Between the tapered back, rounded edges, and strategic bevels it still fits well in my hand and in my pocket. Popping the stylus in and out of its slot is a satisfying fidget exercise, complete with a lovely click.. Many of its contemporaries had plastic styli, so credit to Garmin for not pinching pennies here.

Inside the iQue is a 200MHz Motorola DragonBall MXL ARM9 CPU paired with 32MB of memory, which is comparable to other premium PalmOS devices of its day. A transflective color backlit screen which allows you to turn off the backlight outdoors and still see the display is also class competitive. Ditto its expandable storage and MP3 playback capability. The only downside was price—similarly specced Palm Tungstens or Sony Cliés cost $399, nearly $200 less than the iQue.

But the iQue isn’t an ordinary multimedia PDA. Garmin bragged that the iQue was the first PDA with an integrated GPS, and based on my research that appears to be true. Some mobile phones had an integrated GPS, and there were GPS devices built on Windows CE, but they weren’t PDAs. The first Windows PocketPC with a GPS, the Mitac Mio 168, wouldn’t debut for another year. So was the GPS worth the extra cost in 2003? And is it still useful today?

Inside the iQue

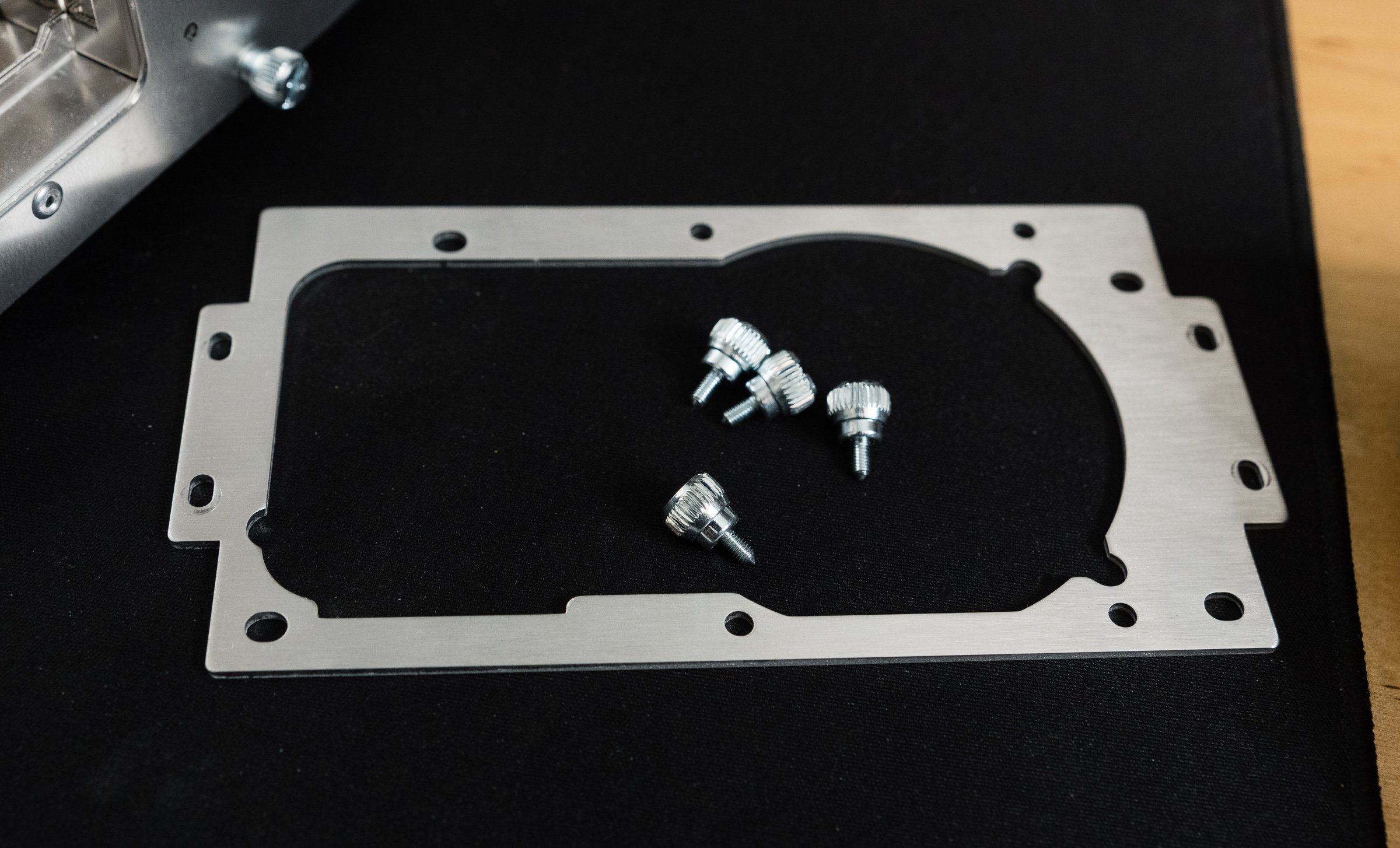

Out of the box the iQue wasn’t very useful because it shut down when removed from its cradle. The first order of business with any portable device old enough to drink is changing its battery. Fortunately, reasonably priced replacements are available on eBay and Amazon. This job wasn’t difficult thanks to an instructional video from NewPower99.com. Now that the iQue can hold a charge, it’s safe to set it up and go mobile.

Setup starts with Garmin’s software CD and a two-disc MapSource map library. Tough luck, Mac users, cause Garmin’s map software is a Windows exclusive. In case you’re missing the installer disc, Garmin’s website still hosts support pages with manuals and software downloads. That’s nice, considering they discontinued support back in 2008. I transferred these installers to an era appropriate host PC: a ThinkPad T21 running Windows 2000.

The downloaded Palm Desktop installer turned out to be a dud because it wanted to download online InstallShield dependencies that no longer existed. I had to fall back to the installer disc which wound up being the same version as the one from the web. After running the disc’s installer, the web installer started working—go figure. I’ve uploaded an ISO to archive.org in case you need it.

Now I need to update the iQue’s OS. Garmin’s firmware support was solid for the era; they released six updates over the course of four years. Pro tip: obey the instructions to the letter unless you want to put your device into a boot loop. After I followed all the steps the device finally started up to Palm OS version 5.2.1r6.

The next step is to install some maps, and the process is similar to other Garmin GPSes of the era. The base map has a 5 mile scale that only shows major highways and byways. To get detailed maps and points of interest you’ll need to install the included MapSource City Select mapping database. It’s a hefty amount of data, totaling over 1.2GB of disk space. Although the iQue supports 2GB SD cards, they weren’t available when it was launched. You couldn’t buy a 1GB card until January 2004 and at $499 it cost almost as much as an iQue itself. Most users methodically managed multiple megabytes of mapping memory by syncing maps as needed or swapping between map sets stored on multiple 128 or 256MB cards.

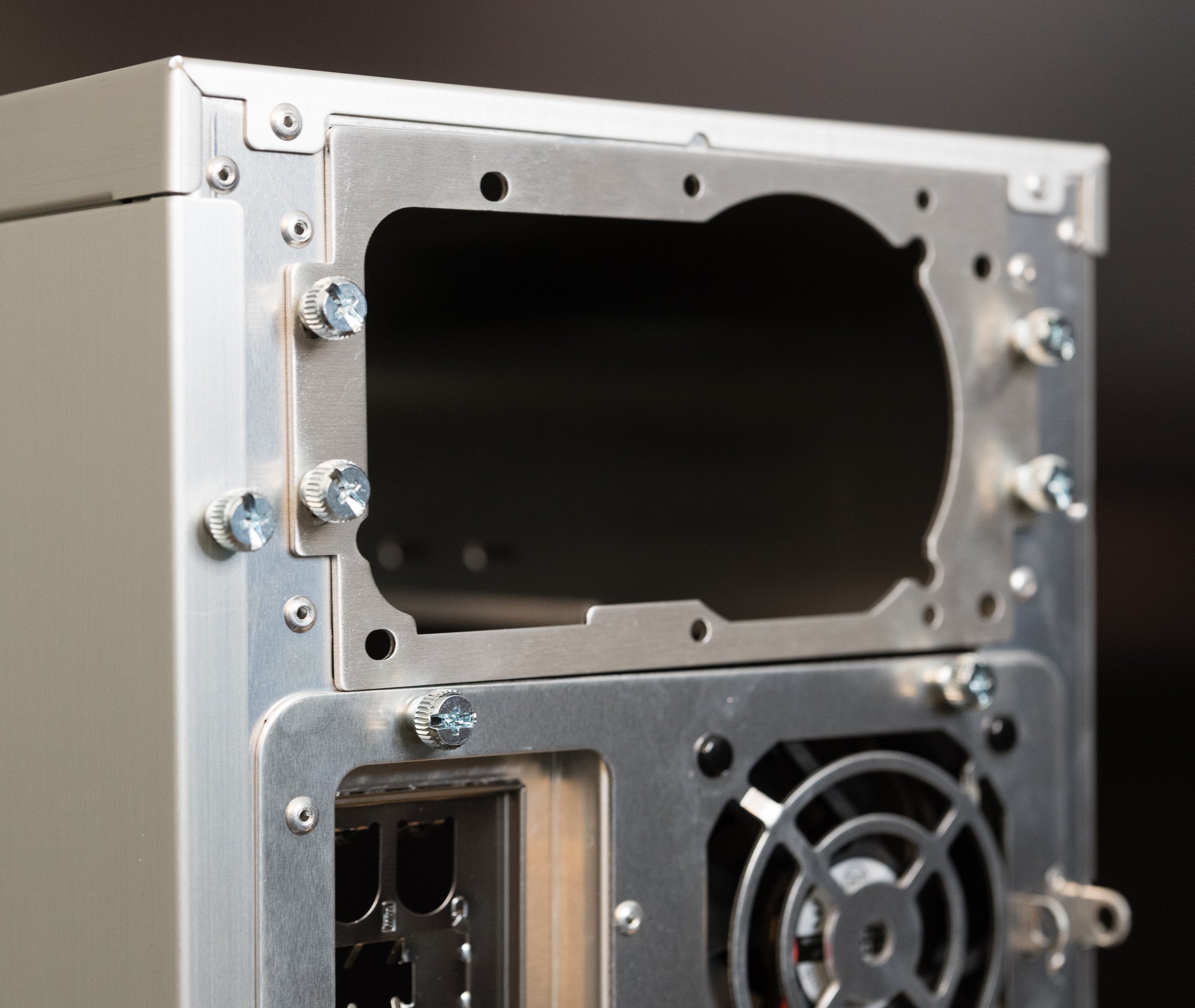

After wrapping up the installations I was ready for an iQue test. This meant going outside, folding out the flip-up GPS receiver, and waiting. This thing has a satisfying thunk when you close it, like a good flip phone. Getting its first satellite fix took a while—almost five minutes. Unlike modern devices there’s no cell tower triangulation or constellation assistance data to speed up this process. But I have good news on the 2019 GPS date rollover front! The clock displayed the correct time after acquiring a fix, which meant Garmin’s engineers either anticipated or fixed the problem—nice.

You can customize this Que button to add or remove apps from the cycle, and by default that’s QueMap, QueTurns, QueTrip, and QueFind. I added the QueRoute controls. If there’s no active route the map will follow along as you’re driving just like a modern phone or GPS. The update rate ain’t exactly great—I figure it’s two, maybe three frames per second at best. The size of the map display is decent, and more can be shown by collapsing the speed and compass overlay. Rocking the scroll wheel zooms in and out while dragging the stylus pans the map.

When you’re ready to hit the road the QueFind app will be your guide. There’s a point of interest database of interesting points like hotels, tourist attractions, roadside services, and more. If where you need to go isn’t in the database you can enter a specific address, intersection, or city name instead. After tapping Route To the iQue generates a list of turn-by-turn directions for your trip.

This experience is surprisingly close to a modern smartphone map app. Maybe not in the presentation standpoint, what with the mediocre frame rate, lack of 3D projection, and pixelated map lines. But from a function standpoint it’s all there. Need to make multiple stops? Use the Add Vias feature. Need to get around road closures or traffic? Go ahead and request a detour. Want a preview of a long trip? Simulated drives are there to guide you. Do you drive a truck, motorcycle, or taxi? Select a specific vehicle type to optimize your routing, even if you’re walking or cycling. Boats and off-roaders aren’t left out either thanks to support for nautical charts and topographical maps. Garmin didn’t hold back—they crammed all the functionality and features of a StreetPilot into a PDA without compromising on user experience.

Rounding out the app suite are programs aimed at traditional handheld GPS users. QueTracks creates a virtual trail of breadcrumbs while the GPS is active, and these logs can be saved as paths to review on the QueMap or downloaded to a desktop PC. Hunt&Fish tries to predict the best time of day for hunting and fishing based on the Solunar theory. Sun&Moon isn’t a Pokémon game; it shows the predicted time of sunrise and sunset, moon phases, and the position of those celestial bodies relative to your location and orientation.

Garmin also extended GPS functionality to other areas of Palm OS. Want to navigate to your favorite bar in the Berkshires? Just open its Address Book card and tap the Route button. Same goes for appointments in the Date Book. You can even attach your current location to a voice memo! We take these integrations for granted today, but in 2003 these were clever and cutting edge.

All these features made for a pretty capable navigation device, so long as you were driving, boating, or walking. But there’s another group that hungered for real-time GPS navigation: airplane pilots! Introduced in January 2005 for $1,099, the aviation-focused iQue 3600A added aeronautical amenities like Jeppesen charts, terrain data, and virtual flight displays. Also included was a yoke-mounted smart cradle with extra controls to navigate the map and input data without using a stylus. And because it’s still a 3600 at heart, Garmin offered the automotive adapter kit which includes the dashboard mount and the MapSource road maps for an extra $200. The 3600A automatically switches between aviation and automotive modes when placed in the appropriate cradle—nice touch!

Navigating with the iQue

Given how advanced the iQue was for its time it raises an obvious question: can it still be useful for navigation today? Let’s hit the road and find out! My regular thrifting route from Wilmington, Massachusetts to Hudson, New Hampshire is a good test route. There’s plenty of twists and turns along a mixture of highways, suburban arterials, and country roads. I know it well enough to judge the iQue’s routing quality, and since the roads haven’t changed much over the past twenty years the old maps should still work.

Planning a route starts with the QueFind app. My hunch that the circa 2004 POI database wouldn’t be helpful was proven correct when my searches returned zero results. Even back then there was always a possibility that the database wouldn’t have what you needed, so I searched for my destinations’ addresses instead and saved them as waypoints. Waypoints are actually entries in the Palm Address Book, which is a clever way to exploit an existing database.

Entering this data was easy enough—search for address, save waypoint, and repeat—but it required my full attention. Being out of practice with Graffiti didn’t help. Doing this in motion would be impossible. At least the rocker can scroll through lists and select waypoints or address book entries. I wouldn’t call the UI sluggish, but it’s definitely not snappy. After creating the waypoints I added them to a route using Add Vias and saved it in QueRoute.

After I activated the route the iQue spent about six seconds calculating turn-by-turn directions, which isn’t fast by today’s standards but it's good for 2003. It dutifully announced my upcoming turns and destinations using voice clips with progressive distances like “in 1.6 miles turn right, in 1000 feet turn right,” and so on. And this guidance comes through loud and clear from the auxiliary speaker built in to the power adapter, even when tucked away in a center console. When you approach that turn the map automatically zooms in to preview the intersection. Combine this with an overlay that displays the current speed, compass direction, and the next turn and the iQue provides a pretty good overview of where you’re going. You can also drive around without an active route and it’ll tell you the name of the road you’re on as well as upcoming cross streets. Overall I’d rate its routing as acceptable, and when I veered off-course it recalculated an update to get me back on course.

The included dashboard mount is well designed and securely grabs the iQue when placed in the cradle. When you’re ready to get out of the car a press of the release button frees it from the cradle with no fiddling required. There’s horizontal and vertical articulation to help angle the iQue for visibility, which you’ll absolutely need because the display’s viewing angles aren’t great. The transflective display puts up a valiant effort but the end result is still a little dim when it can’t catch direct sunlight. It’s still usable but this would’ve been called out in a review twenty years ago. At least the angle of polarization didn’t conflict with my polarized shades. Unfortunately the base wasn’t heavy or grippy enough to stay planted during spirited driving, and I’m sure my car’s smooth pleather dashboard didn’t help.

There’s a couple other gotchas. Even though the resistive touch screen recognizes finger taps, the touch targets like the re-center button are teensy tiny and impossible to activate without a stylus. I, uh, wouldn’t recommend doing that while driving. The iQue also locked up a few times during my journey, and I’m guessing these hangs were thermal related because it felt fairly warm when I pulled it from the cradle. I won’t hold these crashes against it; this is a twenty year old device after all. Thankfully it automatically resumed navigation after a restart.

If someone handed me an iQue in 2003 I would’ve been ecstatic. Back then I was using road atlases and printouts from MapQuest to find my way around in unfamiliar territory. Being able to get instant turn-by-turn directions with live maps from my pocket computer would make me feel like Geordi La Forge. The only thing that compares would’ve been a dedicated unit like the StreetPilot, and those just as uncommon in 2003. And even with its very real 2003-era limitations it’s amazingly close to a modern navigation experience!

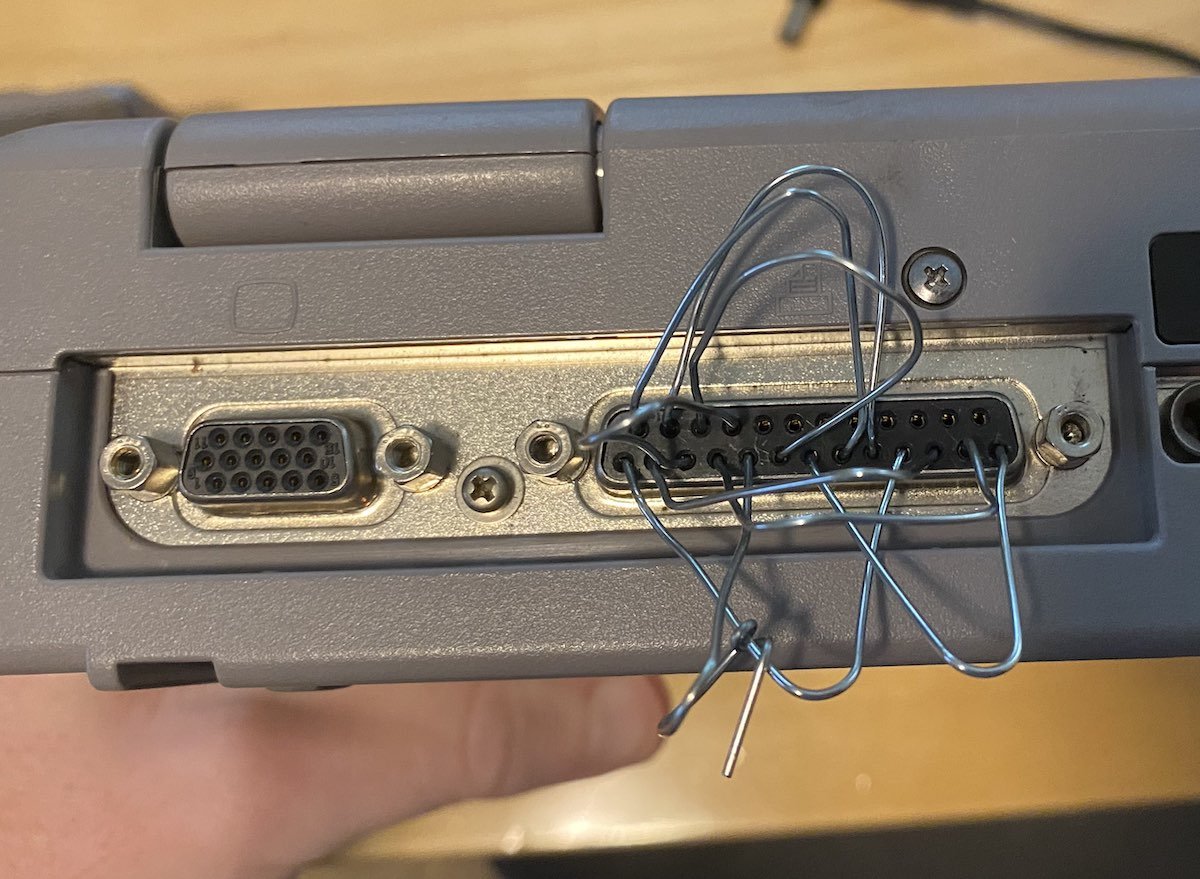

Now while the iQue was the first PDA with integrated GPS, that didn’t mean it was the first PDA to use a GPS. People connected a GPS to a PDA using a serial cable to log their locations, and the GPS makers noticed. They soon unveiled devices designed to attach directly to specific PDA models, and some even offered turn-by-turn navigation. As luck turns out I have one right here: the Rand McNally StreetFinder Deluxe for the Palm V.

Released in the year 2000—three years before the iQue—the StreetFinder has so many limitations that it puts the minimum in minimum viable product. The Palm Vx’s 8MB of memory and lack of SD slot means it can barely hold any map data—and God help you if you have a vanilla 2MB Palm V. Routes and map data must be calculated ahead of time on a desktop PC and then HotSynced, which takes forever over a serial cable. And when you finally hit the road the experience is grade-A jank. There’s no voice guidance for upcoming turns, which would be okay except the pea-green screen isn’t very readable in a car. If you get lost or need to make a detour there’s no dynamic re-routing. And the map display doesn’t move along with you—it’s always north-up and when you reach the edge of the screen it scrolls to a new page. I could go on and on about the limitations of this setup, and I recognize that this was the best they could do at the time given limited memory and processing power. I’m not saying it’s completely useless; it’s that reaching for turn-by-turn navigation was beyond this device’s grasp. If you use it to log data or to show your location on a static map, it’s a similar experience to a serial GPS except it’s easier to connect and takes up less space.

Unlike the StreetFinder the iQue is capable enough that if it had modern maps it could be a viable navigational aid today. So it’s too bad that Garmin stopped publishing map updates for it. Oh egads, my trip is ruined! But what if… I were to load new, up-to-date maps on this obsolete PDA with a GPS? Ho ho ho ho, delightfully devilish, Daniel! There’s plenty of maps on the web in Garmin’s IMG format, or you can roll your own if you’re feeling plucky. I downloaded OpenStreetChest’s database for the Northeast US, which is based on OpenStreetMap data. After installation the new tile set showed up in the Map Installer plugin and I could send them to the iQue’s SD card. The downside is that these maps consume more storage, which means longer HotSync times and more card swapping. The fact that I could load new maps without any trouble is a wonderful surprise—I really thought I’d have to do some hacking to load new data. Thanks, OpenMapChest!

Garmin also created an API so other Palm OS mapping apps like PathAway could use the iQue’s GPS. And it does work! PathAway is more like a traditional map-and-compass setup, perfect for folks who like geocaching, boating, or wilderness exploration. It’s not a turn-by-turn navigation app, so it can’t replace the Que suite, but that’s okay. Because the iQue’s a general purpose device, you can extend its capabilities much like modern smartphones. A StreetPilot has advantages like a bigger screen and car-focused controls, but you’ll never be able to run games or spreadsheets on it. So how well does it wear both hats?

The iQue as a PDA

2003 was a busy year for the PDA market. Manufacturers needed new features to differentiate their devices once color screens were commonplace. They also faced increasing pressure for pocket space from cell phones, MP3 players, and digital cameras. Sony Clies added hardware keyboards, wireless networking, and digital cameras. Handspring created the Treo smartphone by combining the Handspring Visor and its VisorPhone Springboard module into one device. So Garmin embedding a GPS into a Palm PDA was a gambit in line with the overall market trend towards convergence.

The iQue is a PDA at its core, and people bought one instead of a StreetPilot because they needed to do PDA things like managing contacts and appointments. The good news is that Garmin licensed Palm OS instead of rolling their own system. The iQue runs Palm OS 5.2.1 and takes advantage of its many improvements like support for ARM processors, SD cards, audio mixing, and a collapsible on-screen Graffiti zone to give apps more screen real estate. OS 5.2 also introduced the Status Bar, which Garmin customized with Que app shortcuts, the GPS status indicator, and buttons to adjust brightness and volume.

Palm OS users will be right at home with an iQue. Basic organizer functions are fulfilled by the standard Palm app suite. All your favorites are there, like the Address Book, Date Book, Todo list, and Memo Pad. It’s a shame that the iQue came out a few months before Palm completely redesigned their suite for the Tungsten T3, but it’s still perfectly usable. Some default apps, like Expense and Mail, are missing entirely. You could use the bundled Documents to Go spreadsheet app to track your expenses—that is, until the free trial runs out and you had to cough up 50 bucks to keep using it.

The missing Mail app demonstrates the iQue’s blind spot around networking. 2003 was a big year for wireless connectivity for PDAs. SDIO Bluetooth and Wifi cards let small, pocketable devices join networks or tether to a cell phone to receive texts and emails. The iQue 3600 doesn’t support these cards at all, and you must use a cable to physically tether a phone. Even if you wanted to HotSync email for offline reading you’ll need a third-party client. A trial copy of MailToGo is on the installer disc, but I think making users pay for an offline email app is rough.

Garmin also included some non-GPS focused apps in their Que suite, and these are QueClock, QueAudio, and QueVoice. QueClock is a straightforward alarm app that lets you set single or repeating alarms without needing to dive into the Date Book. It also shows the current precise time and your next upcoming event. It should really be a world clock, too, but there’s plenty of those out there for Palm OS if you wanted one.

QueAudio is a bare-bones MP3 player that lets you listen to files stored in an SD card’s Audio directory. There’s no playlists and sorting is very rudimentary, but it does have a shuffle function. It choked on many of my modern MP3 files—I suspect it doesn’t like 48KHz sample rates—so I dug up an old one to give it a test. The speaker’s audio quality is, well, bad, but it sounds fine through headphones. It’s no iPod, but it’s on par with other PDAs.

QueVoice records voice memos when you press and hold the record button. The audio quality isn’t great, thanks to the mediocre mic and the crushing 11KHz sample rate. There’s an option to use ADPCM compression which significantly cuts down on file size without compromising the file’s already rough quality. It works, but don’t use it to record your demo reel.

There’s one last criteria to judge the iQue as both a PDA and a GPS: battery life. And it’s not great! Garmin’s public statements about the iQue’s longevity didn’t inspire confidence. Quote: “approximately 10 days if used an average of 30 minutes per day with backlight off.” I find that answer vague and unconvincing. It’s just like saying my car gets 40 miles per gallon if I always drive downhill and lay off the turbo. More useful numbers are found in the 3600A’s manual, which claims 5 hours of battery life with the backlight set to 50%.

After spending some time with a fresh battery I’m inclined to agree with that five hour estimate. That is, until I turn on the GPS and the battery drains even faster. Reviews at the time were not kind to its battery usage, with CNet calling it “gluttonous.” If you want any kind of reasonable runtime outdoors with the GPS enabled you must forego the backlight and rely on the transflective display. The GPS polling rate can be reduced to save battery, but I would only suggest turning that knob for hiking or walking. Be sure to plug it in to a power port while driving.

Take The Long Way Home

A convergence device often ends up being less than the sum of its features, but that’s not the case with the iQue. It’s a Peanut Butter Cup fusion of Palm PDA and Garmin GPS thanks to good software design. Much like the Treo gave us a preview of our data-connected computer phone future, so did the iQue for our omnipresent navigational device.

I say this a lot, but it bears repeating: part of the fun of the retro experience is using something you couldn’t afford or didn’t know about back in the day. I had PDAs. I had a GPS. But I never had a PDA GPS. And seeing just how much Garmin got right years before location-aware smartphones is uncanny. They might not have known at the time but this was the precursor to how millions—perhaps billions—across the globe navigate their daily lives.

Garmin tried to grow their share of the PDA market by making more models at different price and feature points. In addition to the Palm-based iQues they produced Windows Mobile Pocket PCs like the iQue M5, M4, and M3. If you already had a PDA you could pick up one of Garmin’s Compact Flash or Bluetooth receivers which came with the same suite of iQue apps as the 3600.

But the iQue’s time in the navigator’s seat was short lived. Garmin shipped their last PDA in 2006. Support for all iQue products ended in June 2008, which in an interesting coincidence is the same month Apple announced their first phone with a GPS: the iPhone 3G. I don’t think the iPhone had anything to do with the discontinuation of iQues—other market forces were to blame. PDAs were already disappearing because Blackberries, feature phones, and early smartphones were choking them out of their market niche. Meanwhile the portable automotive GPS business kicked off by Garmin’s own StreetPilot was booming. They became so cheap and useful that regular people were buying them to install into their cars—or buying a car that had a navigation system built-in.

Still, I’m happy to add it to my collection, even if I won’t be using the GPS much. Why have a boring regular Palm when I can have something with a twist? Even if I didn’t have one of these back in the day, I can see the appeal, and I applaud Garmin for showing us how to find our way before it went mainstream.