The Macintosh SE/30 - Computer Hall of Fame

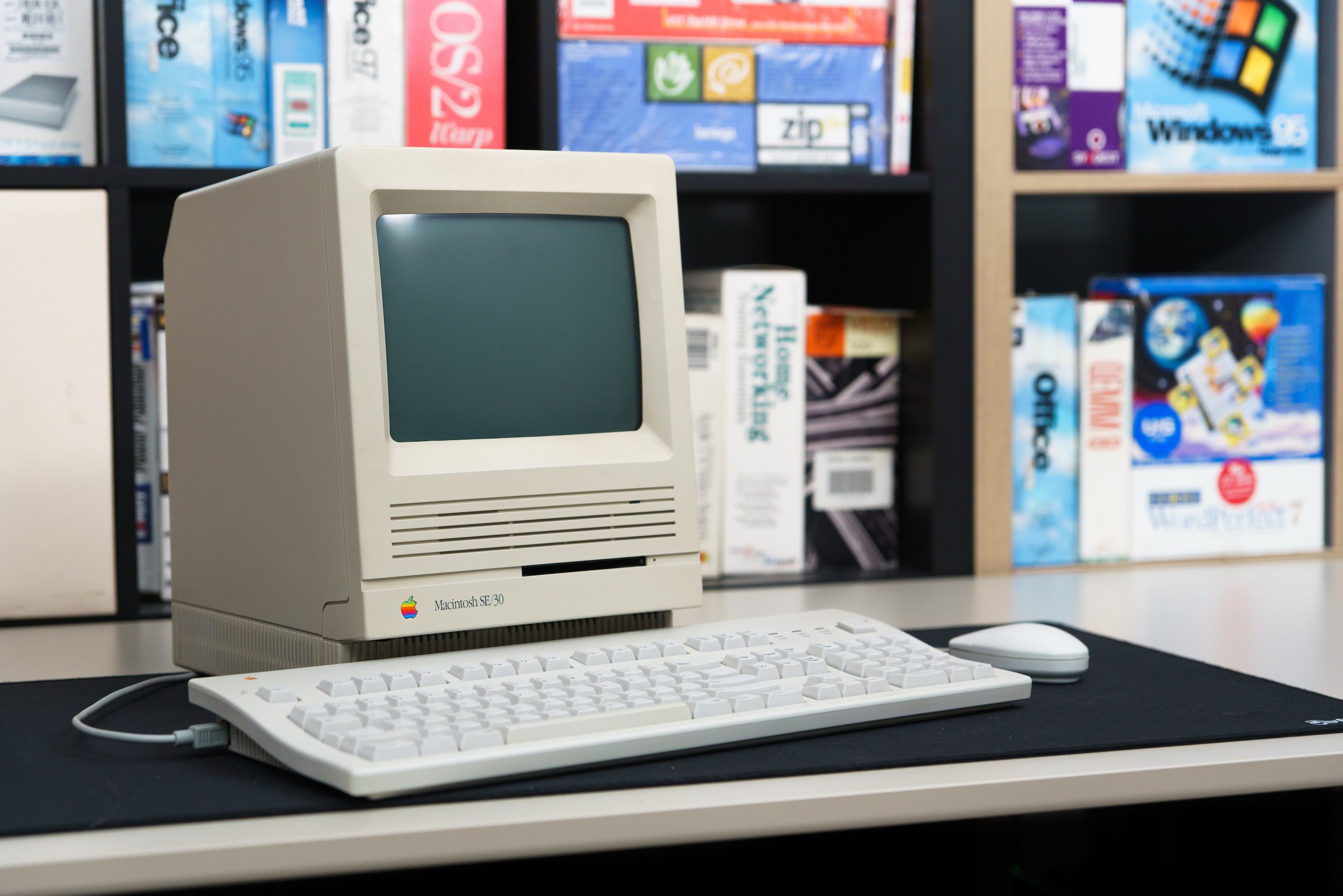

They say never meet your heroes, but every once in a while they live up to the hype. Here in Userlandia, let’s welcome the first inductee to the Computer Hall of Fame: The Macintosh SE/30.

It’s rare these days to find a computer that expresses some kind of philosophy. One example is Framework, whose primary design focus is upgradability and repairability. Compare that to a sea of lookalike and workalike laptops from competitors who can’t articulate why you should buy their machines over another’s except for price. Of course, there’s another manufacturer that makes computers with some kind of guiding philosophy, and that’s the trillion dollar titan: Apple. You might say said philosophy is “more money for us,” and you wouldn’t be wrong! But on a product level, there’s still some Jobsian “Think Different” idealism at Apple Park. To wit, the rainbow-colored M1 iMac still channels the soul of its classic introductory commercial narrated by Jeff Goldblum—“Step one: Plug in. Step two: Get Connected. Step Three… there is no step three.”

2024 will mark the fortieth anniversary of the Macintosh. Not just the Macintosh as a platform, mind you, but the fortieth anniversary of the all-in-one Macintosh. Today’s iMac is vastly more powerful than the original 128K, but both of their built-in displays say Hello in Susan Kare’s iconic script. Another thing they have in common is a love-it-or-hate-it reaction to the all-in-one form factor. A compact Mac, for all its foibles and flaws, sparked something in people. It had personality. But while the Mac was fun and whimsical and revolutionary, something always held it back. Even die-hard fans couldn’t ignore its insufficient memory or inadequate storage, let alone its lack of expansion. Apple crossed off these limitations one by one with the 512k, Mac Plus, and SE.

Only one limitation remained, and that was performance. Inside the SE was the same 68000 CPU found in the original Mac. Sure, it was slightly faster thanks to slightly speedier memory, but that wasn’t enough to satisfy Mac users who wanted a more powerful Mac without spending five and a half grand on a Macintosh II. They turned to third party upgrades like DayStar Digital’s accelerator boards to give their Macs a turbo boost, and Apple took notice. Why leave that money to a third party when they could take it up front?

Apple announced an upgraded SE on January 19, 1989: the SE/30. This upgrade didn’t come cheap—the SE/30’s suggested retail price of $4,369 was a considerable premium over a vanilla SE. But underneath a nearly identical skin was a brand new logic board based on the range-topping Mac IIx. With a 16MHz 68030 processor and 68882 floating point unit, the SE/30 crammed phenomenal computing power into an itty-bitty chassis space. It’s a rare example of Apple actually giving some users what they wanted. An SE/30 could be a writing buddy, a QuarkXPress workstation, an A/UX server, or even a guest role in Seinfeld as Jerry’s computer.

Although I missed the SE/30’s heyday, I experienced it after the fact through books, magazines, and websites. The argument that the SE/30 is the best version of what Steve Jobs put on the stage in 1984 is a persuasive one. Prominent Mac writers like John Siracusa and Adam Engst proclaim the SE/30 as their favorite Mac of all time. They’re joined by decades of Usenet and forum posts from people all over the globe who love this little powerhouse. All this praise has inflated prices on vintage SE/30s, even ones in questionable condition. So when I was given the opportunity to pick one up, complete in box, for free? Now that’s an offer I couldn’t refuse.

One Person’s Mac is Another Person’s Treasure

You never know what treasure’s buried in somebody’s basement. Back in September I was at a work function catching up with a colleague, and I mentioned my trip to VCF Midwest. “Oh, I didn’t know you collected old computers,” he said. “I’ve got an old Mac from the 90s in my basement. It was my aunt’s, and she barely used it. It’s still in the box. Do you want it?” Do I?! Of course I wanted it! A day later he sent me some photos of the box, and I couldn’t believe what I saw: it was an SE/30! It was like somebody told me I could take a low mileage Corvette from their barn. I stopped by his house the following Saturday and picked up the SE/30, an Apple Extended Keyboard 1, and an ImageWriter II all still in their boxes. I couldn’t in good conscience take all this for free, so I gave him one of my vintage Mamiya film camera kits and a case of beer in return.

I’d love to tell you that I brought this Mac home, took it out of the box, powered it on to a Happy Mac, and partied like it was 1989. But you and I both know that’s not how this works. Schrödinger’s Mac might have succumbed to a multitude of maladies during its many years in the box. Even new old stock or barely used gear suffers from aging components, because a box isn’t a magical force field that halts the passage of time. SE/30s are notorious for using explosive Maxell batteries. Surface-mount capacitors have the capacity to leak their corrosive electrolyte all over the logic board. Spindles and heads inside the mechanical hard drive could be seized in place. The only way to know for sure was to open the stasis chamber and bring this Mac out of hibernation.

Outside the box was a shipping label that said this machine was sold by the New York University bookstore, which was one of Apple’s pilot universities for selling Macs to students and teachers. Inside the box is the SE/30 along with a complete set of manuals, some software, and a mouse. Up first is the open me first packet, containing the system software and tour disks. Bill Atkinson’s HyperCard comes standard for your stack-building pleasure. All the manuals and extras are there too, like the QuickStart guide, quick reference sheet, Apple stickers, and even the “Thanks for buying a Mac” insert. There’s even a a bonus copy of Microsoft Word.

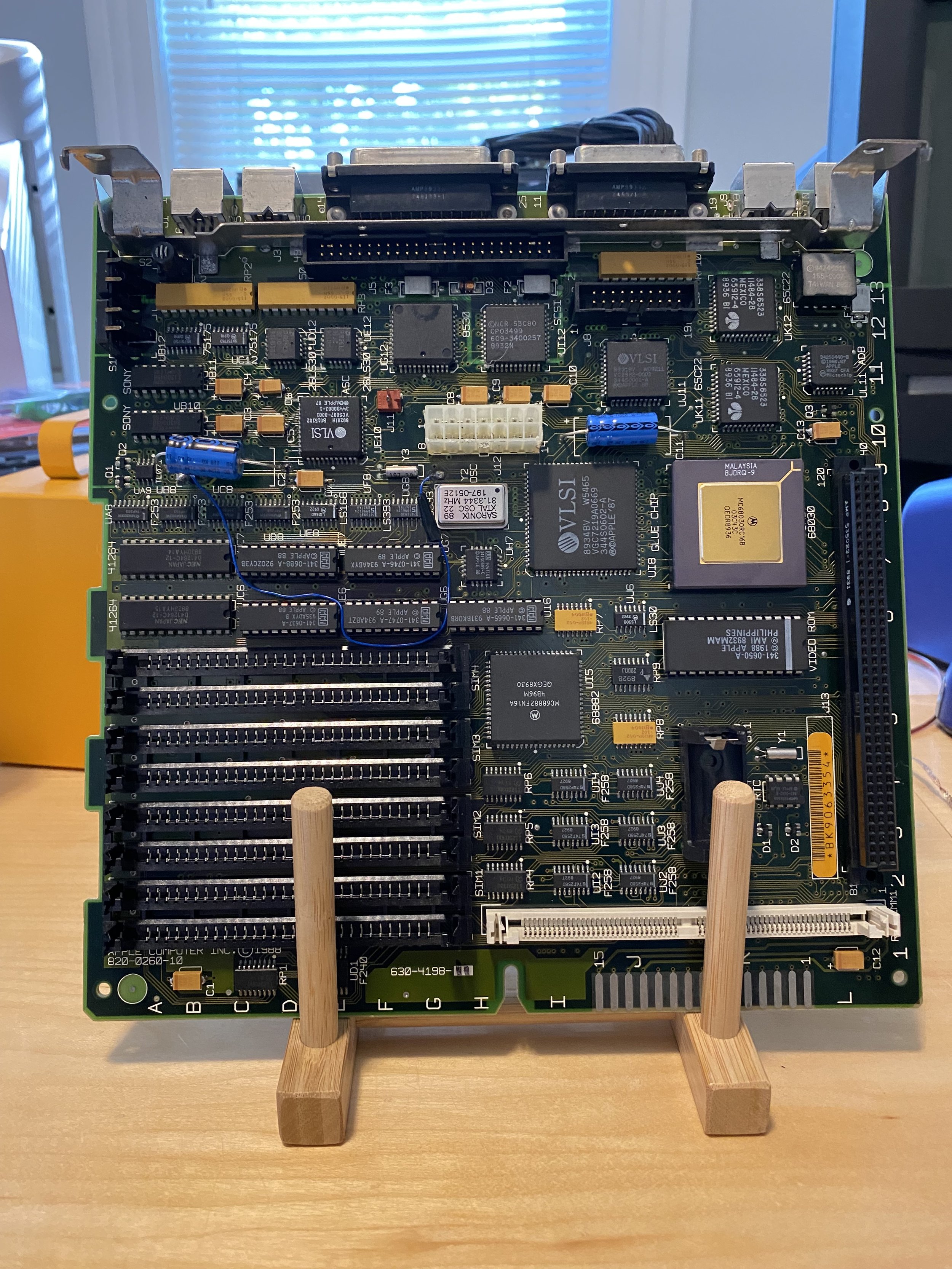

Fully recapped board

Manuals and accessories are nice, but what you really want to see is the Mac itself. This SE/30’s case looks pretty good for a computer old enough to have a midlife crisis. The keyboard and mouse have yellowed a bit more, but it’s nothing a retrobrite couldn’t fix. But how it looked outside mattered less than how it looked on the inside. I cracked open the case to inspect the condition of the logic board. The intact purple Tadiran PRAM battery exhibited no signs of leakage—phew! A light coating of crud clung to the capacitors, which meant a recap job was in order. Barely any dust covered the boards and cables, and the CRT had none of that notorious black soot. The analog board capacitors showed no signs of bulging or leaking. Honestly, this is really good condition for an unmaintained machine of this age. I thought my odds of a successful power-on test were very good. I plugged the board back into the Mac and turned it on. Unfortunately, it powered on with a garbled screen colloquially known as simasimac. This condition could happen for a variety of reasons, but the prime suspect was those cruddy capacitors. After a date with a soldering iron and some tantalum caps, the newly recapped board was ready for another test. I flipped the switch and got a familiar bong—now this Mac is a Happy Mac. Success!

Maximizing My Macintosh

While the recap brought the SE/30 back to life, it wasn’t ready to head back into action just yet. This machine was a bone-stock configuration, and it would need some upgrades to unleash its full potential. My coworker’s parent’s sibling’s former Macintosh came equipped with 1MB of RAM and a 40MB hard drive. That was Apple’s mid-range config for the SE/30, but one megabyte of memory was a bit stingy for a machine that cost over four grand in 1989. The 40MB SCSI hard drive was more appropriate for its price, and I wouldn’t mind keeping it if it worked. Alas, I couldn’t rouse it from its decades-long slumber. Thankfully, both of these problems are easy to solve for the modern vintage Mac owner.

Mass storage was first in the lineup, because the hard drive was ding-dong-dead. I needed a better solution than another SCSI hard drive—even if found a compatible drive, it’d just as likely to die as this one. I turned to the current champion of modern retro storage: BlueSCSI. The external DB-25 model is an okay solution, but an SE/30 deserves internal storage. I could have mounted it on the same bracket used by the internal hard drive, but that would mean cracking open the case every time I needed to put something on the SD card. The solution is PotatoFi’s 3D printable PDS slot bracket. Now I can access the SD card from outside the case and even see the BlueSCSI’s status LEDs. Brilliant!

Batting second was RAM. An SE/30 can address a maximum of 128MB of RAM when all eight memory slots are populated with 16MB SIMMs. This stood as the record for the maximum memory inside an all-in-one Mac until the Power Mac 5400 in 1996. Few users actually took advantage of that high ceiling because 16MB SIMMs took a long time to come to market, and when they did, they were outrageously expensive. Nowadays they’re cheap as chips, as my British friends like to say. There’s plenty of eBay shops selling 64 and 128 meg kits for $50 and $100, respectively. Or you can get them from Other World Computing for a similar price. 128MB felt like overkill, so I bought a 64MB kit and saved the difference.

RAM

I snapped four new SIMMs into four empty slots and flipped the power switch. The Mac booted up to the desktop and About This Macintosh displayed a total of 65MB. Hooray! But—there’s always a but with old computers—there’s more to the memory story. Many old Macs, including the SE/30, run a memory test on a cold boot. Stuffing your SE/30 full of RAM will have a significant impact on the duration of this test. A maxed out SE/30 can take a minute or two to go from power on to Welcome to Macintosh, and a 64 meg system takes half as much. But that’s not the only caveat for large amounts of memory. The SE/30, along with the II, IIx, and IIcx have a dirty secret—a 24-bit dirty secret.

Have you ever thought about what defines the bit-ness of a CPU? If I polled the average retro computer enthusiast as to how many “bits” are in the Motorola 68000 CPU inside their Amiga 500, Atari ST, or Mac SE, they’d likely answer “16-bit.” Sega used the 68000 in the Genesis and advertised it as a 16-bit system. And they’re not wrong, but they’re not completely right either. To understand how Apple’s ROMs got so dirty, we have to understand the development of the 68000.

The year is 1976, and Motorola Semiconductor was in a heap of trouble. Sales of their 8-bit 6800 microprocessor were slumping due to stiff competition from the likes of the 6502, Z80, and 8080. Meanwhile, Intel’s marketshare was soaring thanks to their advancements in silicon fabrication. They were already designing a new 16-bit CPU, the 8086, that would leapfrog the 8-bit competition. Now Motorola’s plans to reinvigorate its flagging CPU sales were at a crossroads. They could rush a me-too 16-bit product to market, but it wouldn’t be able to beat Intel on price or performance. Having determined that fighting Intel head-on was a losing bet, Moto would zig where Intel had zagged.

Colin Crook, Tom Gunter, and the 68K team decided that a 32-bit instruction set would be a way to future-proof their design while offering something Intel wasn’t. There was only problem with this clever idea: economically packaging all the support circuitry for a full 32-bit CPU wasn’t yet possible. A dual-inline package CPU with more than 64 pins was costly both in manufacturing and in board real estate. So how could they keep an eye on the future while utilizing then-current tech?

Motorola’s solution was implementing the 32-bit 68K instruction set with 16-bit components. The CPU has 32-bit registers, a 32-bit memory model, and 32-bit data types, but it also offers 16 and 8-bit data types. Only 24 of the 32 address lines are connected to memory, and the data bus and arithmetic logic unit are 16-bit. This let the CPU use those common 64-pin DIP chips. Most programs used the 8- and 16-bit instructions, with 32-bit operations possible if you were okay with reduced performance. This forward-thinking architecture made it easy for Motorola to design a full 32-bit chip, unlike Intel who needed to work around a lot of cruft when designing the 386. 68K software would be forward compatible with Motorola’s eventual full 32-bit chip, so long as you didn’t do anything foolish like hijack the unused high-order memory address bits for non-addressing purposes.

Unfortunately Andy Hertzfeld did exactly that when he designed Mac OS’ lockable and purgeable memory flags, to his later regret. The memory pointer had room for all 32 bits, but only 24 were actually used because only 24 physical memory address lines were available on the CPU package. Exploiting this seemed like a good idea at the time; those eight bits weren't doing anything and it’d be an efficient use of limited resources. But that quest for efficiency in the present mortgaged their future, and the bill came due when Apple shipped Macs with 32-bit 68020 and 68030 CPUs. These 24-bit dirty Macs couldn’t address more than 8MB of RAM unless you used A/UX.

Apple fixed this memory malady by including new 32-bit clean ROMs in Macs beginning with the IIci. Application developers also had to fix their apps to avoid touching those memory address bits. Owners of the II, IIx, IIcx, and SE/30 expected Apple to offer a ROM upgrade to unleash their systems’ full potential, but Apple never did. Most users back in the day fixed this limitation by installing a 32-bit patch extension like MODE32 or Apple’s 32-bit Enabler. If you were lucky to find a spare Mac IIsi ROM SIMM, you could install that into your SE/30 and have a truly 32-bit clean compact Mac. But those ROMs were hard to find back then and are even rarer today.

Instead of stealing Peter’s ROMs to fix Paul’s Macs, the community has developed new hardware to clean up Apple’s dirty laundry. I procured a Big Mess O’ Wires ROMinator II, which is one of several modern Macintosh ROM SIMMs. It’s not only 32-bit clean, it also eliminates the memory test, adds a ROM disk, and a few other features. I’m not sure how I feel about the pirate icon and the new startup chime, but I admit it gives the Mac a little more character. If you don’t care for the frills, a GGLabs MACSIMM or a PurpleROM will get you 32-bit cleanliness and a ROM disk for a lower price. Honestly, running Mac OS 7.6 and later on these machines without an accelerator is probably a bad idea. I’m sticking to System 7.5 and earlier.

After the repairs and upgrades, the SE/30 was ready for a test drive. I wrangled words in Microsoft Word, slummed around in SimCity, and floated with AfterDark’s flying toasters. Apple claimed the SE/30 was four times faster than a vanilla SE and it sure feels that way. My past experiences with a Plus, SE, or Classic left me wanting because applications always felt a little slow. Not so with the SE/30—its responsiveness, especially with solid state storage, was excellent. I had to admit I was falling for the SE/30’s charms. I get it now. It’s not just hype or nostalgia—this was the compact Macintosh as it was meant to be, without compromises or excuses. So why did Apple kill it?

SE/30/30 Hindsight

Apple discontinued the SE/30 on October 23, 1991. Its replacement, if you could call it that, was the Classic II. The headline specs for the Classic II sound like an SE/30 in a cheaper package. It had a 16MHz 68030 CPU, 2MB of RAM, and a 40MB hard drive all for the low cost of $1900. Sounds like a good deal, so what’s the catch? While the Classic II’s 68030 ran at the same clock speed as an SE/30, it was hobbled by a 16-bit external data bus, making it 30% slower than an SE/30. Floating point calculations are even slower because the FPU was now an optional add-on. Two, its maximum RAM was cut down to 10MB—a fraction of the SE/30’s 128MB. Three, the versatile PDS slot was replaced with a more limited connector for that optional FPU. All these changes combined to make the Classic II more of an entry level appliance and less of a power user’s machine. SE/30 fans were understandably upset; they wanted an upgrade. Why would Apple kill a beloved Mac like the SE/30 without offering a true successor?

A lot changed at Apple from 1989 to 1991. Jean-Louis Gassée—Apple’s product man responsible for high-cost, high-powered Macs like the IIfx and the Mac Portable—left the company in 1990. CEO John Sculley and newly promoted COO Michael Spindler delivered new marching orders to Apple’s engineers: build less expensive computers to grow Apple’s marketshare. From that standpoint the Classic II was a smashing success. The SE/30’s copious component count made it a prime target for a cost-reduced revision. The Classic II’s highly integrated logic board had 60% fewer chips than the SE/30’s, making the Classic II considerably cheaper to manufacture while maintaining a healthy margin. The street price for an SE/30 with 4MB RAM and 80MB hard drive in 1991 was $2800. A Classic II with the same specs was $2400, and one year later Apple’s retail partners would sell the same machine as a Performa 200 for $1200. Slashing the maximum memory and removing the PDS slot pushed power users to more expensive Macs instead of buying a Classic II and hot-rodding it.

The Color Classic wasn’t the upgrade SE/30 owners were looking for.

By 1993 the black-and-white Mac was looking pretty dated in a world of Super VGA graphics. It had been four years since the announcement of the SE/30, and its fans picked up on rumors of an upcoming all-in-one color Mac. Surely this time will be different and they’d get the upgrade of their dreams. And when the Macintosh Color Classic was announced, it looked it might be the one! It came in a brand new case featuring Apple’s curvaceous Espresso design language and a glorious ultra color Sony Trinitron display. Apple even brought back the PDS slot! But wait—further down on the spec sheet was the same old and slow 16MHz 030 hampered by a 16-bit data bus. And a maximum of 10MB of RAM, again? It’s not different at all, is it, Steve?!

Apple soon realized their mistake and launched the Color Classic II a few months later with a 33MHz 030 and a full 32-bit data bus. Now this was a true upgrade for most SE/30 users, but Apple didn’t sell them in the USA. Too bad, so sad. Apple was descending into its beleaguered era, when prospective Mac buyers had to choose between the dizzying array of Centrises, Quadras, Performas, or whatever Apple’s roulette wheel said they should name their computers on any given day.

But wait—you’re a discerning power user with an SE/30 on their desk. Why should you spend multiple thousands on a new Mac when you could spend multiple hundreds on an accelerator instead? DayStar Digital’s Turbo 040 sold for about $1500 in 1993. As long as you were still okay with monochrome video, this card gave your little Mac enough power to trade blows with the reigning heavyweight champion, the Quadra 950 tower. And if you weren’t okay with monochrome video, Micron’s XCeed brought multiple shades of gray to the SE/30’s display. Color graphics cards were available too. A determined user could hack together an accelerator, graphics card, and network card into this tiny package and keep it going until the PowerPC transition finally made them cry uncle and buy a new Mac.

Apple’s power users have been remarkably loyal to the Mac through some pretty tough times. Not necessarily loyal to Apple, mind you—I have a hunch that the kind of people who owned SE/30s bought Mac clones. But these people stuck with the Mac through the beleaguered era, eventually becoming the bloggers and podcasters who filled the vacuum left by the death of Macworld, MacUser, and MacAddict. Whenever there’s a new Mac announcement I always sense this undercurrent from their coverage that “if only Apple made a computer tailored to my specific needs, it would be the best computer ever! Just like the SE/30, and the Cube, and the G4 towers!” But like it or not, the Macintosh and Apple are no longer the underdog who’s too cool for school. You’d think they’d be happy, because Apple finally won and took over the world, but they can’t be happy because Apple lost their counterculture joie de vive in the process.

The SE/30 Abides.

I understand why so many former SE/30 owners have been chasing that machine’s ideal for decades. Perhaps it’s an impossible standard to live up to and their idea of the Perfect Mac can never actually be realized. After all, the SE/30 had its share of shortcomings. But in the context of the overall package they were minor inconveniences. It’s no surprise that it found an audience with college students, writers, and designers who appreciated aesthetics and the value of the overall package while appreciating its technical prowess. If I had one at the time, I would’ve appreciated it too. Sometimes when you meet a hero, you’ve actually met the real deal.