What’s Inside A NeXT Computer Accessory Kit?

Here in Userlandia, we’re entering the NeXT dimension.

Ah, NeXT. Now there’s a corporation as lousy as it was brilliant. With their bold black hardware, their object-oriented software, their memorable marketing—and unfortunately, their problematic pricing—NeXT workstations were unlike anything the competition put out. Steve Jobs often bragged that the NeXT was five years ahead of its time—hence the name. But being ahead of your time is no guarantee of world domination—just ask the creators of the Amiga. After five long years selling very few of its very expensive computers, NeXT retreated from the hardware business and shuttered its highly automated Fremont factory. It survived as a software company long enough to be acqui-hired by Apple in a last-ditch effort to save the faltering Macintosh. RIP NeXT Computer Corporation. It died as it lived: spending Ross Perot’s money.

Death for corporations is as certain as it is for humans, but unlike with humans, it doesn't have to be the end. Like your favorite underappreciated artist, NeXT was far more successful after its demise. Every Apple device sold over the past twenty-ish years runs an operating system based on NeXT software. More people know about NeXT today than ever before because of Apple's miraculous turnaround after Steve Jobs rejoined the company. That awareness, combined with the trendiness of retro computing, means a hot market for old NeXT gear. Even a non-functioning NeXT looks good on a shelf. But actually getting a NeXT on that shelf is easier said than done. According to my sources—which, annoyingly, don't cite their sources—barely fifty thousand NeXT computers were actually sold. Most were used in corporate or university settings, which makes finding complete examples even more difficult because institutions have a tendency to sell off unused hardware. The spooks at the CIA loved NeXT machines, maybe theirs were melted down.

Victory at the Auction!

But owning hardware isn’t the be-all and end-all of the vintage computer hobby. Tons of peripherals, software, manuals, merch, and media are ready to move in with your old computers. The best way to find this memorabilia are places like swap meets and vintage computer shows, and that’s how I acquired the subject of this episode. Listed in the 2022 VCF Midwest Auction preview was a “Complete NeXT Cube Documentation Set.” “Big deal,” I thought, “it’s just some manuals.” But when it came up for bids, I realized I was wrong to judge an item by its listing. It was actually a complete accessory kit for a first-generation NeXT Computer. This NeXT box contained not only a complete set of documentation, but also software, warranty cards, setup sheets, and the famous NeXT computer brochure. Topping it off was a sheet of NeXT logo stickers, and I’m a sucker for shiny stickers. If no one else had been interested, I could have walked away with it for a mere $50, but apparently I'm not the only one with excellent taste in antiquated computer paraphernalia, and after an honest-to-god bidding war, I paid $270. A small price to pay to support the convention.

Discovering a complete-in-box NeXT Cube or NeXTstation might not even be possible these days. I thought the same thing for a complete accessory kit. This accessory box might be the closest I ever come to getting a new NeXT computer. But buying a new computer isn’t just about the computer—at least, not for me. It’s also about the experience of setting it up and settling in. That means perusing the packaging, browsing the booklets, and enjoying the extras. It’s the same vibe you get when opening up an old big-box computer game and combing through all the feelies. NeXT certainly obliged on this front, providing a hefty accessory kit that held everything you needed to get started.

The NeXT Brochure

Opening the box reveals the famous NeXT computer brochure. Granted, the NeXT brochure has long since been scanned and uploaded, but actually holding a real one is a different experience. This particular example shows some signs of use but it’s in otherwise excellent condition. Actual-sized photographs of the one-foot cubic computer adorn the front and back covers, giving you a taste of what’s to come. Each page is printed on heavy 100 to 120 pound satin text paper, which is almost as thick as the cover. This isn’t some throwaway piece—the designers wanted you to treat this brochure with respect.

In keeping with NeXT's intended user base of academics, the brochure opens with a thesis statement. A NeXT Computer was, and I quote, “the yardstick for measuring computing in the nineties.” This remarkably persuasive argument plays out over twenty-six pages, describing seven unique features. The actual-size depictions continues with the system board and storage sections. These cutting-edge creations are impressively captured in a full-scale full-color reproduction. Each component on the NeXT board is purposefully arranged in a model of engineering elegance where no square inch is wasted. That’s due to an overwhelming usage of surface-mount components. NeXT invested millions of dollars developing an automated assembly robot that could pack both surface-mount and through-hole components closer than ever before. That’s old hat today, but cramming this many circuits and components on to a board was cutting edge in 1988. It was complete overkill, of course, and this very expensive automaton would become a symbol of NeXT’s delusions of grandeur. But it’s hard to argue with the actual finished product. If circuit boards could be art, this would be it.

Magneto-optical didn’t kill the hard drive star.

Turning the page brings us to a magneto-optical disk, which still looks kind of futuristic, even thirty years later. Both the board and cube are tough acts to follow, and the marketing copy makes a case for the disk by promising vast rewritable storage that wasn’t chained to one computer. You could transform any NeXT cube into your own computer by popping in an optical disk with your own OS, documents, and applications. Unfortunately, this first-generation Canon MO drive didn’t live up to the hype. It was slow and unreliable, which are bad qualities to have in a boot device. No other computers used the format—it was proprietary—so exchanging data without a network or an external disk drive was literally impossible. Even if you had the non-NeXT version of that Canon MO drive, it couldn’t read NeXT disks. NeXT quickly abandoned the MO drive and pivoted to floppies, CD-ROMs, and networked storage. The only legacy of that optical disk today is, of all things, Mac OS' "busy" cursor. Yes, that spinning rainbow beach ball was originally a spinning magneto-optical disk.

More impressive than magneto-optical disks was the Motorola 56001 Digital Signal Processor. A DSP endowed every NeXT computer with powerful 16-bit 44.1KHz sound playback and recording capabilities. Every app in NextStep had access to the DSP’s digital audio and MIDI music capability thanks to the included SoundKit and MusicKit frameworks. Sadly, the brochure is only paper, and can’t convey the difference between CD-quality digital sound and the 8-bit 22KHz that most PC sound cards were capable of at the time. The brochure also claims that the DSP can be used for all sorts of things, like emulating a fax modem entirely in software, or controlling a very impressive array of external devices. While there were DSP-specific add-ons like imaging boards and sound samplers, my reading of old NeXT newsgroups and modern NeXT forums indicates that most NeXT users never plugged anything into their DSP ports.

PostScript for both display and print.

Software also gets its due, with the Display PostScript engine billed as the next generation of “What You See Is What You Get.” By using PostScript for a device-independent display model, the same commands used to print were also used to create the computer’s display—a revolutionary idea at the time. NextStep’s window server could combine high-resolution raster images, vector graphics, and outline fonts to render a high-resolution display that far outclassed a Windows PC or Mac… as long as you were okay with grayscale. NeXT wasn’t the first to utilize a device-independent display—look up Sun’s NeWS for a contemporary competitor. But since Display PostScript was an official Adobe product, it gave NeXT serious graphical bonafides. DPS, like the MO drive, was an attempt to disrupt the status quo. But unlike the MO drive, DPS was more successful, even though it wasn’t exactly speedy and NeXT took a lot of heat for not initially supporting color. Speed improved over time and NeXT did announce color machines in late 1990. DPS was replaced by the PDF-based Quartz in Mac OS X, which carries on the legacy of a device-independent display layer.

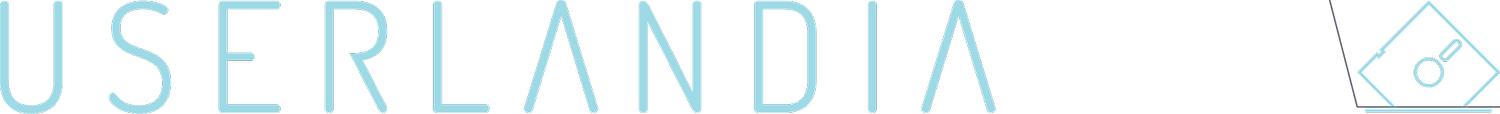

UNIX for Mere Mortals

Another familiar quote is “UNIX for mere mortals.” Other UNIX systems had GUIs, but NextStep was arguably the easiest one to live with on a daily basis. It had all the benefits of a multitasking, multithreaded, protected-memory environment with ease of use that rivaled a Macintosh. You didn’t have to use a command line to get your daily tasks done, but it was there just in case. Apple used the same exact sales pitch when OpenStep became Mac OS X, which appealed to a new wave of techies and developers who previously overlooked Macs.

The software story continues with several pages about NextStep's bundled applications. The parallels to Mac OS are noticeable, with today's Dictionary.app serving as the heir to NextStep’s Webster and Digital Library. Same goes for NextStep’s e-mail application, to which Mac OS’ Mail.app still bears a passing resemblance. It was the most advanced e-mail system you could buy in 1989, and Steve loved demoing NeXTmail and its advanced features. Combine that with WriteNow—a full-featured word processor—and you could be writing your dissertation minutes after setting up your NeXT.

Developers! Developers! Developers!

Last in the brochure are pages discussing software development and NeXT’s third-party partnerships. NeXTstep’s application framework kits allowed developers to spin up custom applications in no time by using common code objects. Then, after you built the app, you created the UI in Interface Builder by dragging and dropping controls on to a window template. This was the most revolutionary part of NextStep, but it only got one page of copy! Mac OS and iOS still use this framework methodology, and other visual toolkits have copied NextStep’s philosophy with varying degrees of success.

Third Parties Will Surely Come, Right?

The final page is NeXT’s closing argument, restating their thesis that they have created a new standard of computing. Endorsements from leading third-party developers project an air of legitimacy, as does retail sales support from BusinessLand—which was ultimately that company’s undoing. Lotus is making a spreadsheet! Adobe is porting Illustrator! FrameMaker will be there too! And it’s true that all these apps eventually shipped for the NeXT. But that's the problem: eventually. Jobs and NeXT were perpetually behind schedule. It was a classic example of Steve Jobs' hubris. He thought he could bring this into existence by sheer force of willpower, Green Lantern-style. He thought that once everyone saw it, they would agree and say "oh yes, this is brilliant!” The brochure concluded by saying the NeXT decade had already begun, which is just begging to disappoint

The Quick Setup Guide

But that's in NeXT's future. We're pretending to be in NeXT's present. We're done thumbing through the brochure, and now it's time to set up our new cube. We won’t have to do it alone, because the Quick Setup card is here to help. An overhead photograph shows a complete NeXT computer system with each cable numbered in the order you’re supposed to connect them. It’s a nice picture, but as a step-by-step guide it’s a bit weak. There’s no flow to the layout, and that triggers my comic book page layout sensibilities. Your eyes ping-pong around the page instead of naturally flowing from left to right. Or you’ll follow the steps at the top and ask “where’s number four again?” because the numbers don’t stand out on the page. Despite everything Steve Jobs ever said about functional design, this is a case of aesthetics over practicality.

A Library of Documentation

Next comes a reminder that this box wasn't advertised as "unopened", just “complete.” Instead of the standard three-prong IEC power cord, there's some thin ethernet terminators and jumpers, and a laser safety data sheet. "Do not look directly into the laser with your remaining eye" indeed. The magneto-optical drive does have a laser in it, but this datasheet has the word "printer" on it, so it's probably from a NeXT laser printer's box. Maybe that's what I'll get at the next auction, no pun intended.

NeXT Documentation Library

With the miscellany out of the way, we’re left with a pile of documentation. These books are less fancy than the brochure, but they’re still quality examples of late eighties documentation. As far as I can tell, these NextStep 1.0 manuals aren't anywhere online, so this might be the first time you've seen them. Maybe I'll get myself an overhead scanner for Christmas, so I can put them on archive.org without damaging their binding. All the books follow NeXT’s minimalist packaging style, featuring plain white covers, Helvetica Italic type, and a giant NeXT logo. Hey, when you’ve got a logo that good, you place that cube front and center.

First in the stack is the Registration, Warranty, and License booklet. Your introduction to NeXT documentation cheerfully reminds you to fill out your warranty card and make sure all your doodads and thingamabobs arrived safely in their boxes. If you fill out the registration card as intended, and can find a mailbox that goes to 1989, you can get a free NeXT t-shirt, which is an offer I wouldn’t have refused. Inside the license booklet are illustrations of the contents of the NeXT computer box, the NeXT accessory kit, and the MegaPixel display box. And yes, I can confirm that everything except for the power cord is in this kit. NeXT tried to get away with a mere 90-day warranty on the original NeXT computer and accessories. If you weren’t satisfied, a NeXT dealer or service provider could sell you a one-year extended warranty for $600 plus the reseller’s markup. Not including hard drive coverage, of course—that’s another $300 plus markup! And remember, all these prices are in 1989 dollars. I’m sure Steve Jobs thought that was a bargain. NeXT eventually realized that expecting people to accept a 90-day warranty on a ten grand computer package was pushing their luck. Newer models had warranties for a full year.

Batting second is the Getting Started booklet. If you skipped—or, more likely, lost—the Quick Start sheet, this guide helps you connect your NeXT computer and peripherals. It also introduces the basic concepts of the NextStep GUI, Workspace Manager, and the Laser Printer. The guide’s user tutorials cover the basics of using a graphical interface, which was still novel in 1989. If you were new to computers, this guide would get you comfortable with using your NeXT in about an hour.

A more advanced user might dive right into the thickest tome: the NeXT User’s Reference Manual. This 460-page book is admittedly pretty dry, but it's well-written for a computer manual, and exhaustively details included applications like the Workspace Manager, NeXTmail, and the WriteNow word processor. This book’s got your back when you need the steps for building a bootable optical disk, pruning the print queue, or finding forgotten files. In addition to NextStep there’s several chapters about the care and feeding of the NeXT computer and peripherals. Need to peek inside that ominous black cube to add some memory or change the clock battery? There’s a complete walkthrough for disassembling the cube, and port pinouts for the technically curious—like you!

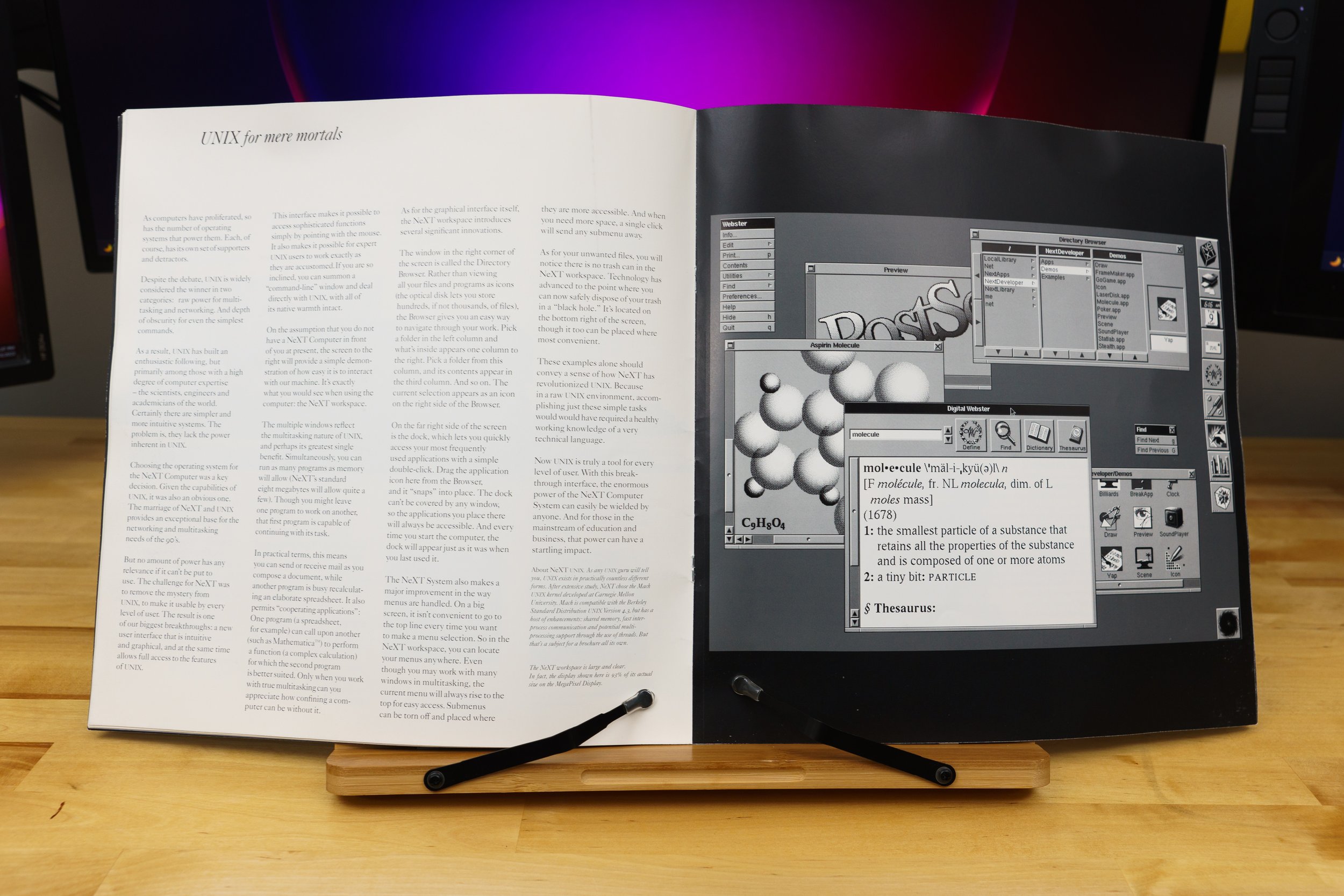

If you were in charge of a network of NeXT computers, the Network and System Administration guide was up your alley. This manual guides you through setting up Netinfo, the directory service that NextStep used to locate other servers, manage user accounts, and enable network booting. NeXT developed Netinfo instead of licensing Sun’s Network Information Service, because Sun was, at the time, their bitter rival. NetInfo hung on until Mac OS 10.4, and this material might look familiar to you if you were a Mac network admin around the turn of the century.

Last but not least is one of the more interesting booklets: the Release Notes. Printed in November 1989, this is the last-minute stuff that missed the deadline for the Getting Started or User’s Reference manuals. NeXTstep 1.0 was famously late and a little rough around the edges, and I’m not surprised that there’s a nine page booklet full of uncomfortable little admissions. Here’s a few of the more humorous ones.

Initializing an optical disk appears to freeze the Workspace Manager. Don’t panic! The highlighted menu item means it’s busy, you see, and for some reason there was no dialog box with a progress bar. I couldn’t find that reason on record anywhere, but I’m sure there was one. So be patient.

A period on its own line in an email message is interpreted as the “end” of the email by NeXTmail. Anything after that gets ignored. Period, end of story, I guess.

If you print to a network printer and the job fails with an error, you have to abort the print job on both the client and server before anyone can print again.

Don’t choose an invalid startup device. Apparently 1.0 didn’t hide unavailable boot options, and you could easily put your NeXT in an unbootable state if you picked the wrong one. So don’t accidentally choose NetBoot when your machine isn’t connected to a network. The only way out is using a magic key command to enter the ROM monitor, and then typing in the code to boot from another device. Good luck.

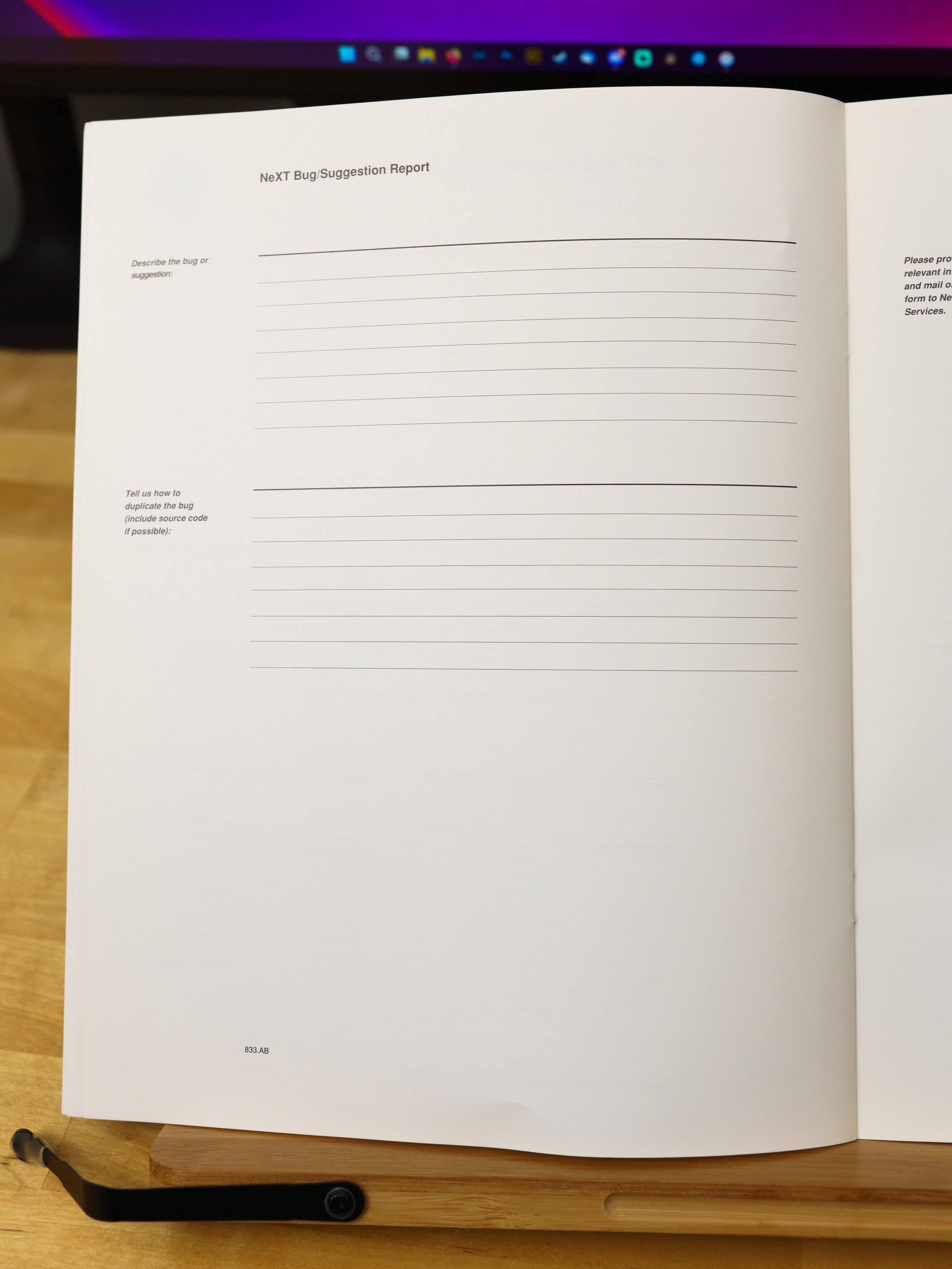

If you happen to run into a problem not mentioned in this long list of limitations, NeXT helpfully provided two feedback forms at the end of the booklet. Simply mail or fax your bug report to Redwood, California and they’ll get right on it.

Stickers and Stuff

And now, the part you've all been waiting for, the reason why I spent way too much money on this box of stuff. Behold: a letter-sized sheet of NeXT logo stickers! With fifteen stickers across three different sizes, NeXT really wanted you to slap their logo on everything. Compare this to Apple, whose contemporary sticker sheet gave only gave you four stickers. I’m very fortunate that only one sticker’s been used from this sheet, and that it was one of the smaller ones. The previous owner apologized for the missing sticker, but I told him it was okay. Stickers are made for sticking, and I’m lucky that he chose one of the little ones.

The NeXT Generation of Stickers

Now, I know what you’re thinking. “Why did you spend so much money on those stickers when you can buy stickers from some rando on Redbubble?” Well, there’s some advantages to the genuine article. If you look closely at most of the NeXT logos on the web or on knockoff products, you’ll notice that they just swiped a flawed logo from Wikipedia. It’s got the wrong colors and a non-uniform gap separating the sides of the cube. Symmetrical means all sides have to be the same! These stickers are actual, 100% accurate NeXT logos, and that satisfies the fussy little designer in me. Amusingly, despite my fussing about Wikipedia having a slightly wrong version of the NeXT logo, I didn't think to check that they still had the slightly wrong version. On November 14, a few days before I recorded this episode, Wikipedia user DigitalIceAge extracted a clean version from a copy of the press kit on archive.org. Thank you, DigitalIceAge. Nice to know I'm not the only one who cares about that sort of detail.

But let’s say you’re okay with a mildly inaccurate NeXT logo. After all, there’s very few genuine NeXT stickers out there, and I recognize that most people aren’t as picky as I am. I don’t begrudge them their knockoffs, because the market abhors a vacuum. If Apple won’t supply NeXT merch, someone else will. But even if you don’t care about the accuracy of the logo, you might be wondering about the construction of these stickers. How do they compare to a knockoff? First, these stickers are solid spot-color inks based on vector artwork. The linework is sharp and the colors match the Pantone swatches selected by Paul Rand. Second, they’re clear, not white, so there’s no distracting borders. Third, they’re vinyl and not paper, which makes them significantly more weather resistant.

I’ll grant that a lot has improved in sticker printing technology over these past thirty-odd years. We’ve got magical direct-print inks that don’t need fussy flexography or sensitive silkscreening to make a durable, water-resistant design. Redbubble will happily sell you stuff printed on clear or white gloss vinyl. But the wildcard is fade resistance. If you’ve used one of the old rainbow Apple stickers, you know that they eventually fade under the sun’s unforgiving ultraviolet rays. These NeXT stickers would likely do the same even if they used fade-resistant inks, but that process usually takes years of outdoor abuse. Redbubble vinyl stickers are printed with UV-resistant inks, but I’ve yet to get one that’s lasted more than a year outdoors without fading significantly. Still, $280 buys a lot of knock-off stickers. When they inevitably fade, you can slap on a new one. Not so much with these genuine NeXT stickers—once they’re gone, they’re gone.

There’s three items of interest left in the accessory kit, and two of them are these magneto-optical disks. One is blank, the other is a system software disk for installing NextStep on a hard drive. I didn’t have MO disks of any kind in my collection until I bought these, and now I’ve got some of the most infamous. While NeXT’s MO disks may have missed the mark, the technology was still used for many years as a high-capacity archival format. The lesson here is that even the most promising tech can fall flat if circumstances are wrong.

The Magneto-Optical Disks and the Hex Wrench

And last, but certainly not least, is a NeXT-branded hex driver. Odds are most users won’t have a hex driver to loosen the cube’s screws, and NeXT solved this problem by including one. Why they did that instead of using Phillips or Torx screws—well, I assume they had a reason, but like with the absence of a disk initialization progress bar, I haven't been able to find anyone willing to go on the record about it. Its handle is molded in the same angular fashion as the cube and MegaPixel display, with distinctive ribs and—ooh, fancy—a NeXT logo. It’s even got a ball-point at the end—not a pen, obviously, it's a little thingy that doesn't seem to have a technical name other than ‘ball-point.' These normally help hex drivers fit in tight spaces, but those clever engineers at NeXT figured out another use. Check the reference manual and you’ll see that you’re supposed to use the ball end to help pull the system board out of the case! Just snap the ball head’s groove into the conspicuous hole on the bracket and pull out the board. Sure, you can use your thumbs, but where’s the fun in that?

Now that we’re left with an empty box, one question remains: was this worth almost three hundred bucks? I could have bought an actual computer for that much money, but this is rarer and neater. Perhaps that’s flimsy post-hoc justification, but it’s nice to have something genuinely rare to call my own. None of this stuff is particularly useful on its own, except for the stickers and perhaps the hex driver. But something doesn’t have to be useful to be collectible—it can be appreciated in the context of its time. NeXT was on a mission to redefine computing, and in spite of its troubles and Steve Jobs’ flaws, the enduring legacy of NeXT in Mac OS and iOS proves that they got something right. These accessories and extras were expressions of that mission, and this box shines a seldom-seen light on that past. All that’s left is to find a NeXT cube and complete the set.